Professional Profile

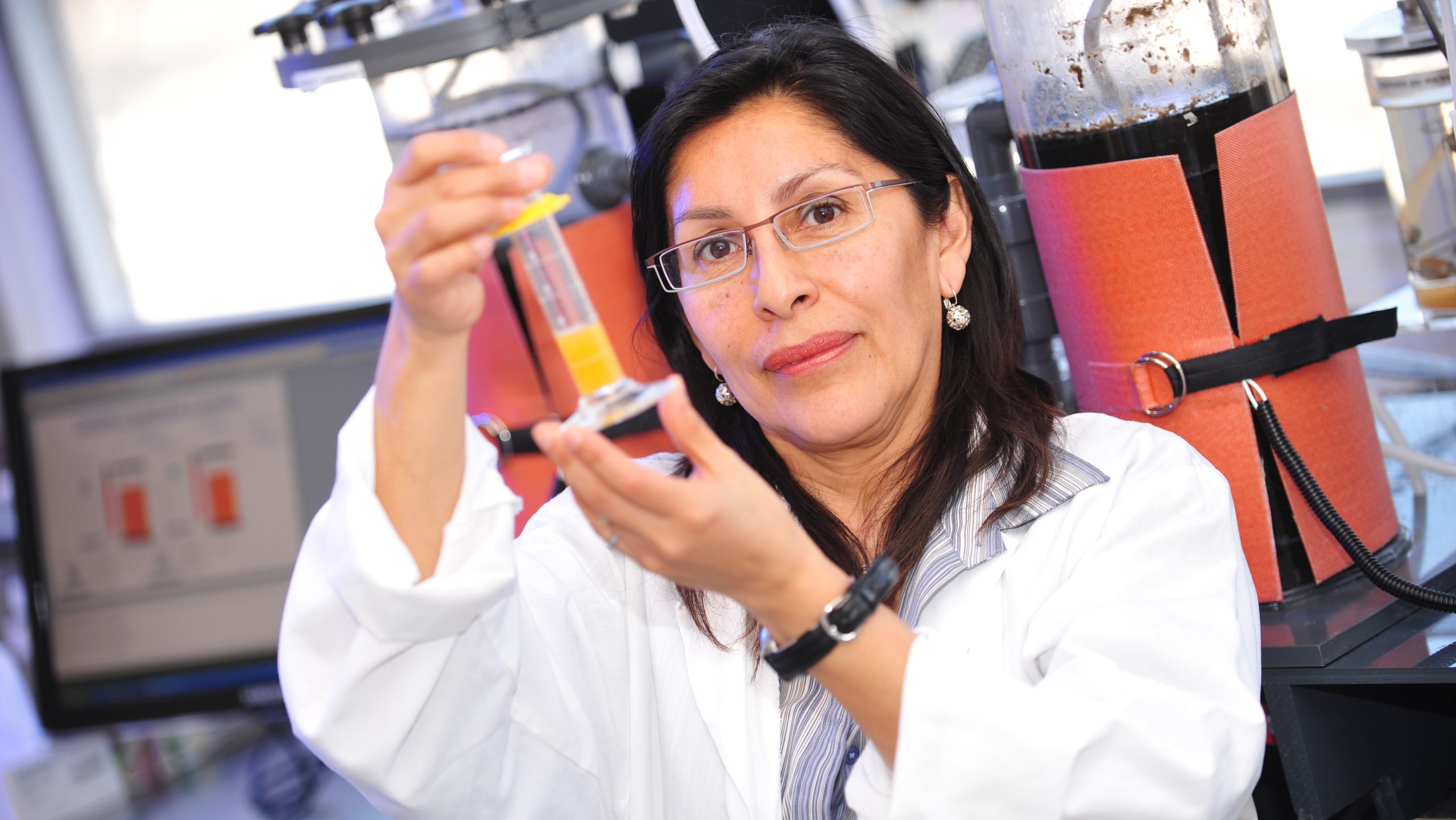

Senator Rosa Gálvez is one of Canada’s most prominent voices on climate change, environmental justice, and social equity. Born in Peru and trained as a civil engineer, she emigrated to Canada and built a distinguished academic and public career.

As dean of engineering and professor at Université Laval, she became widely recognized for her research on pollution, environmental contamination, and urban sustainability, as well as for mentoring new generations of engineers and researchers.

In 2016 she was appointed to the Senate of Canada, becoming one of the first Latina women to hold that role. From the Senate she champions energy transition, sustainable finance, and environmental protection, combining scientific rigor with a humanistic vision. She has received multiple awards for her leadership and for her advocacy on behalf of vulnerable communities facing the climate crisis, embodying integrity, knowledge, and a commitment to a fairer and greener future for Canada and the world.

Born in Peru and living in Canada for almost five decades, Senator Rosa Gálvez describes herself as an immigrant, mother, engineer, researcher, and senator. Her biography weaves together the laboratory, the classroom, and public service. With the image of a gardener of causes, she explains how sowing ideas in science, communities, and institutions demands patience, rigor, and perseverance.

The story begins with ink and paper. As a teenager in Lima, she replied to an invitation to correspond with a young man from Quebec. Eight years of letters sustained a friendship that eventually became a meeting in person. He traveled, in principle, for a couple of weeks and stayed for a couple of months. They married and, once in Canada, he encouraged what she had always loved: studying. Gálvez followed that impulse and pursued postgraduate studies at a respected university in Quebec, where she also began to teach. That academic door became her path into the country and into a professional space where her technical vocation could dialogue with a broader interest in the environment.

Today she prefers to define herself with a simple image. “I describe myself as a gardener, a gardener of causes,” she says. In her metaphor, ideas are seeds and the soil is multiple: the laboratory, the community, institutions. “You plant seeds in the lab, you plant seeds in the community, you plant seeds in politics. Some germinate quickly, others take years. It requires patience and dedication.” She organizes her biography by stages rather than titles. “First I was an immigrant, then a mother, then an engineer; then senator and researcher.” She summarizes her sense of belonging with an image that returns again and again: walking with two feet, one in the Andes and the Amazon, and the other on the banks of the St. Lawrence River.

Integration, she says, happened through college and work. While she was still studying, she was already teaching and training as a researcher. Then came offers that marked a crossroads: a company opening environmental impact assessment offices; an invitation from the World Bank to work in New York, at the World Trade Center; and the possibility of remaining in academia. She chose to research and to teach, focusing on environmental engineering. She was drawn to what she calls hybridization in research, building bridges between disciplines to better understand complex problems.

The path was not without friction. “I have faced many, very big challenges,” she acknowledges. One of them repeats itself over time: entering rooms where decisions are made in science, engineering, community spaces, and now in the Senate, and feeling the weight of an atmosphere dominated by male voices, sometimes marked by prejudice. “Every time you walk into those rooms, it is a challenge,” she recalls. Her response has not been to withdraw, but to sharpen her tools. “You come out with experience, learning how to argue, to defend, to use softer or firmer strategies depending on who you are speaking with.” Humor also helps. “A sense of humor, ironic and satirical, has helped me,” she confesses, to ease rigid spaces. And she repeats a reminder like a mantra: “I am here for what I am worth.”

Another word runs through her story: invisibility. “We can be everywhere, and yet we are invisible,” she says of Latinos in Canada. She remembers that when she moved to a small town on the banks of the St. Lawrence, “I was the only Latina, the only immigrant, the only person of color.” Often, people assumed any origin except Latin America. The way forward, in her experience, combines conviction and direct contact: holding firmly to one’s own story and, at the same time, offering a warm smile to melt the ice in institutions with rigid hierarchies.

Her love for mathematics and reading was there from the beginning. “I like cooking, the garden. I have always been an athlete, and I like reading books on politics, economics, and the environment,” she says. Environmental engineering became a space where method meets the real world. From her formative years she carries a lesson that marked her: when a campus opens doors based on merit, jobs come to the university and skills are considered before accent, gender, or skin color. That foundation nurtured a trajectory that led her to teach large groups, lead research teams, and participate in spaces where technical evidence helps shape concrete solutions.

The transition to public institutions came later, without rupture. As a senator, she prefers to speak about responsibilities rather than positions. Sometimes, she admits, the symbolism can feel heavy. “Sometimes it is overwhelming,” she says, when audiences place excessive expectations on her. To explain herself, she turns to another image: “I am someone who has a flashlight and advances in a dark forest. If one person follows me, I am happy; if there are a hundred, even better.” The central task, she insists, is to show a path and to share what has been learned so that those who come after do not feel alone.

That gesture of accompaniment runs through her daily work. In her office she has received young people who ask how it all happened, what challenges and opportunities she faced, and also people who arrive with very vague ideas about how an institution works. Her response is to open processes, explain routes, and ground expectations. She avoids pedestals. “There is nothing extraordinary or exceptional about me,” she says matter-of-factly. The difference, she suggests, lies in being attentive to opportunities and accepting the invitation to leave the comfort zone.

This is the advice she often repeats to Latin American women who arrive with big dreams: “You learn a lot when you are in a comfort zone.” Beyond the familiar there is risk, yes, but there are also persistence, resistance, and resilience, strengths that only emerge in new scenarios. “We do not know what we are worth until we place ourselves in situations where these indicators appear,” she sums up.

In her everyday life, Latino identity is not an accessory but a practice: warmth to open doors, discipline to sustain efforts, and curiosity to read beyond the immediate perimeter. Her training, she notes, was nourished by different languages and texts, including Portuguese, Italian, and technical manuals in other languages, and that openness still guides her way of staying informed. She values networks, friendships spread all over the world that help her contrast realities. She carefully observes the role of technology in public conversation and the need to maintain criteria for distinguishing reliable information. She sees enormous potential, for example in artificial intelligence applications in medicine, and at the same time insists on using it responsibly.

At the community level, one of her satisfactions is having helped secure the recognition of October as Latin American Heritage Month in Canada. She saw this as a step to go against invisibility, to show that the community not only celebrates through cuisine, humor, and culture, but also works, is active and dynamic, and contributes to the well-being of Canadian society in multiple fields. She is interested in strengthening that presence with more references in academia, justice, public life, and environmental stewardship, and with greater connection among people who share different roots.

When she reflects on what is still missing for more Latinos to access decision-making spaces, she mixes hope with realism. “There are still very few of us,” she acknowledges, but she also sees encouraging signs: people beginning to occupy places in local politics, in sustainable finance, in civic initiatives. That collective sum matters to her because, she says, “we bring another way of reading things,” diverse life experiences, languages, networks, and readings that expand the field of vision. For those who arrive with the urgency of a shortcut, she helps to place their feet on the ground. There are no magic formulas, she insists, only sustained work, study, and community.

In the end, the image of the gardener returns, not as decoration but as method. Sowing ideas in science, in communities, and in institutions requires perseverance. Caring for them demands rigor. Learning from them calls for openness. With that compass she has crossed laboratories, classrooms, and the halls of the Senate. With that same compass, she says, she will continue to walk with one foot in the Andes and the Amazon and the other on the banks of the St. Lawrence.