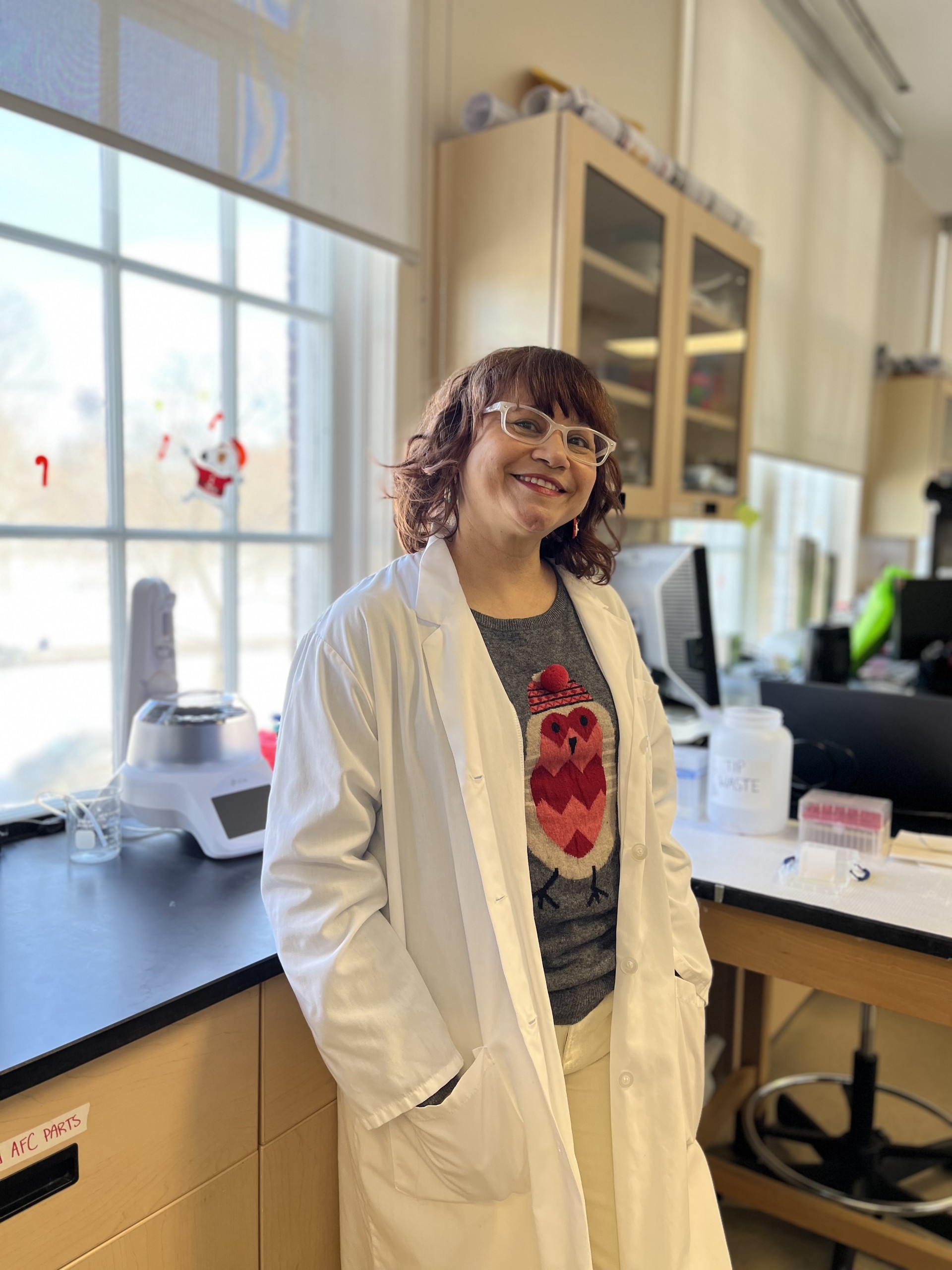

Professional Profile

Alicia Viloria-Petit is a Venezuelan biologist trained in immunology and cancer biology, based in Toronto, Ontario. After arriving in Canada in 1996 for a research internship, she continued her academic trajectory with a PhD at the University of Toronto and built a career in research and education grounded in perseverance, scientific rigor, and mentorship.

Alongside her scientific work, she leads an online STEM mentorship and guidance program for young Latin Americans. Operating in English, French, and Spanish, the initiative reaches participants across 18 countries and focuses on expanding awareness of STEM pathways while providing practical tools such as scholarship applications, networking strategies, and professional development.

Sometimes a life changes in an airport corridor. Alicia Viloria-Petit remembers the flight on which, while returning from visiting the family of her Canadian boyfriend, she leaned over to speak with a researcher who worked in cancer, the same field as her thesis. There was immediate rapport. She talked about her experiments, her excitement for science, and what she was writing. When the plane landed, he handed her a business card. Later, when she looked up his name, she realized she had been speaking with one of the most recognized figures in cancer biology.

She sent him a draft of her article. That same day, an invitation arrived: a four-month internship in his laboratory, with expenses covered, framed as both a test and an act of trust. It was 1996. She came to Toronto, worked in the lab, and as the internship ended, a second invitation followed: stay for a PhD with a scholarship through Canada’s federal research system. “He told me not to go back, to stay and do the PhD in his lab,” she recalls.

The trajectory that led to that moment began in Maracaibo, Venezuela: undergraduate studies in biology and then a master’s in immunology at the Venezuelan Institute for Scientific Research. Before the airplane story, another coincidence reshaped her horizon: she met her now husband, a Canadian, at the institute’s student residence. That relationship brought Canada closer to her future long before she arrived.

Toronto welcomed her with a mix of support and diversity that, she says, shaped her adaptation: extended family in the city, a laboratory with students from multiple countries, and a supervisor focused on attracting international talent. “I was doing my thing, doing what I wanted; I felt like I was in heaven,” she says. Still, there were hard adjustments: distance from family, sporadic phone calls, and the long winter, with a lack of daylight that hit her unexpectedly. “One day I started crying for no reason… it turned out to be the lack of light,” she remembers. Learning to protect her emotional health became part of the journey, alongside scientific training.

Her arrival does not match the most common migrant narrative. She had funding, a support network, and a clear place to begin. She does not present that as a personal merit badge. She names it to acknowledge that not everyone lands with the same support, while also making clear that the path was not easy. Laboratory life is relentless in its own way. Cultures fail. Contamination can erase months of work. Experiments refuse to replicate. “At first it was difficult,” she admits, describing competition and the pressure to produce. Over time, she built a calmer relationship with experimental failure. A negative result, instead of closing the story, can open another door. “At this point… I see a negative result and it doesn’t affect me at all,” she says.

Alongside research, she observed Canadian academia through the eyes of someone living multiple intersections. Being a woman, Latina, and accented, she says, creates “an intersection of minorities.” She does not describe overt hostility, but subtle bias in decision-making spaces. In meetings, her ideas were sometimes ignored until repeated by a colleague. In one instance, she named it directly: “He just said the same thing I said five minutes ago.” That calm clarity changed the dynamic. She also recalls insinuations about whether she “deserved” to be in a high-level lab. Her response was consistent: evidence, work, and strategies to assert her voice without internalizing other people’s doubt.

She frames her leadership around two traits she connects to her Latin identity: sociability and resilience. “I communicate well with people… I’m very sociable,” she says, and that helps her teach, lead teams, and speak publicly. The other side is the ability to navigate complexity. Growing up in Latin America, she explains, gives perspective and gratitude for the concrete opportunities offered by Canada’s research and scholarship systems. That gratitude became a form of commitment: not only to advance personally, but to open paths for others.

Nearly five years ago, that commitment took shape as a virtual mentorship and guidance program for young Latin Americans interested in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. Today, she says, it operates in English, French, and Spanish and reaches 18 countries. The model is dual: broaden students’ understanding of what STEM careers can look like, and provide practical tools to navigate the system, including scholarship applications, differentiation strategies, and network-building.

She speaks about scholarships with lived experience. During her training, she obtained 18 awards, she says, five of them full and the rest partial. That know-how became workshops where she shares application criteria, storytelling strategies, and curated lists of international opportunities. But beyond the numbers, she insists, it is the stories that sustain her.

She mentions one young Haitian woman who, in a context of extreme insecurity, joined the program thanks to her English, volunteered, and later coordinated the French branch. Today, she studies at the Université de Montréal with a scholarship, combining mathematics with a projected path into economics. She also points to participants from Colombia, Bolivia, and Venezuela who, as she describes, have accessed studies or employment in their fields. One contributor moved into sports journalism in the United States after collaborating with the initiative. “That’s what motivates me the most: seeing that it works,” she says.

When she advises a young Latina newly arrived in Canada who dreams of science, she returns to the practical: find a mentor. She speaks from direct experience supporting students who reach out through referrals from other migrant families. The support, she emphasizes, is not only academic. Many newcomers arrive carrying trauma and psychological strain. Part of mentoring, in her approach, is helping them identify mental health professionals and community networks, while also teaching them how to navigate a different institutional culture, admissions processes, and expectations.

Looking at the Latin community in Canada, she sees steady growth in visibility and civic dialogue, including with provincial and federal institutions. She also identifies a recurring barrier: credential recognition for professionals trained abroad. She does not offer simplistic solutions or timelines. Instead, she favors direct engagement: showing up when possible, asking questions, and advocating for more agile pathways to validate degrees without lowering standards.

She aligns her program with the Sustainable Development Goals and emphasizes that scientific progress is not only medical or technological, but also social. For her, diversity is not a slogan. It is a driver of innovation and a practical advantage in labs, universities, and companies. Her biography functions as proof: a funded internship that became a PhD, a career built on method and perseverance, and a choice to translate lived experience into opportunities for others.

She does not idealize science, which can be fiercely competitive, nor migration, which can hurt through absence and distance. Still, in both she has found the space to practice what she values most: perseverance with purpose, the discipline to repeat an experiment until a signal appears, and the decision to share the door once it opens.